My student wants to play chamber music, but doesn't trust his sight-reading skills. They are in fact, he says, non-existent. He is not a born sight reader, but his ear is good. I've found over the years that most pianists are proficient in one, but not both of these skills. Of course, there are a few who have both skills. We are allowed to dislike these people very much.

My student wants to play chamber music, but doesn't trust his sight-reading skills. They are in fact, he says, non-existent. He is not a born sight reader, but his ear is good. I've found over the years that most pianists are proficient in one, but not both of these skills. Of course, there are a few who have both skills. We are allowed to dislike these people very much.When someone is a good sight-reader, it means they are able to bring the score to life at first look,

making it sound like the piece. Some pianists, I've noticed, think that sight-reading means being able to read music. If one can read music, of course, one is using the eyes to do so. But poking out notes a few at a time is not what I call sight reading. A good sight reader learns to automatically associate the passage on the page with its location on the keyboard without passing through the intellect. This is the crux of sight reading.

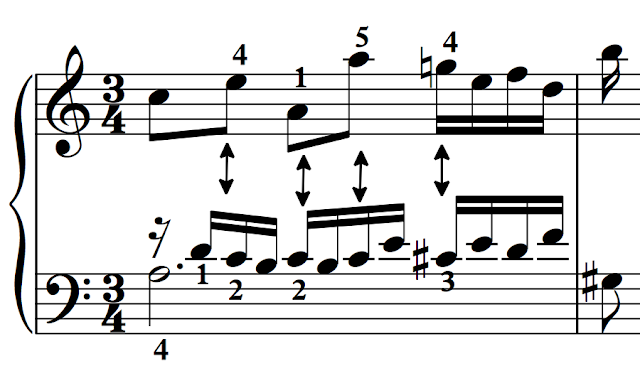

Now for an about face. There is really no such thing as sight reading, that is if one has at least some experience with notation. By that I mean the

process of reading music fluently can be reduced to simply recognizing a finite (probably?) number of patterns, repeated over and over again in various permutations. I know, this is not really very helpful. There are, however, exercise volumes addressing this very concept, deadly dull, mind-numbing whole pages of patterns to play repeatedly. Never mind. You don't need them.

But do learn to recognize patterns. Our common practice music is made up largely of

scales and arpeggios. Look for these. Our music is also largely made up of tertian harmony, so learn to feel shapes of chords and their inversions. This will help with Alberti figures, too.

If you want to systematically work to improve your sight-reading skill, here is a plan:

1. Do it. Every day. Set aside ten minutes of practice time. Really. Every day. I know it is not satisfying to have to do something that seems

incomplete. Keep scores handy that are much easier than you are capable of actually playing. A hymnal is a good place to start, as hymns are mostly homophonic. Or Anna Magdalena Song Book. Or easier sonatinas or other Classical-era teaching pieces.

2. Scan. Before beginning, look through the piece. Look for any surprises, i.e., change of key or meter, technical challenges. I do this myself when someone hands me something I don't know.

3. Tempo. Decide on a tempo that

accommodates the quickest note values.

4. Continue. Begin to play keeping track of the pulses and don't vary. If something goes wrong, don't stop. Go on to the next beat or the next measure. If this happens often, the tempo may be too fast.

5. Focus. Keep eyes on the page and don't look down. There are many great blind pianists, so we know it is not necessary to look at our hands. Did I say keep eyes on the page? This is important.

6. Anticipate. As you are already keeping eyes on the page anyway, you might as well look ahead. It doesn't help to continue to stare at what you've just played. This is particularly wise at ends of lines.

7. Find a partner to read with. This is a good

way to force yourself to continue. A partner who reads well and is willing to play simpler music with you is ideal. There are also collections of teacher/student four-hand pieces. (I've published some of these myself for just this purpose. Look for them in the column at the right.)

For this study, it is okay to "sight read" the selection two or three times. And as always, try to see everything—dynamics, articulation—and enjoy the music.