|

| Clara Schumann |

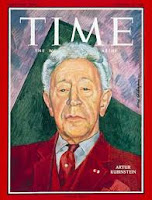

A recent article by Tim Page in the New York Times, Clara Schumann and Her Pupils, brings to light a recent release of old recordings by pupils of the great Clara Schumann (1819-1896), arguably the first piano diva. Her pianistic descendants have much to say about her teaching and her milieu, including hobnobbing with Brahms, Liszt and the like. She was "one of the most soulful and famous pianists of the day," according to Edvard Grieg and is credited with virtually inventing the piano recital as we know it today. She was one of the first to perform in public without the score, a shocking thing to do in 1830 and something that caused a stir. In addition to her extensive concert career, she was wife to Robert, mother to eight children

|

| Clara Schumann |

and a respected composer. And letters! Did she ever write letters. Thousands, apparently. She corresponded with the musical greats of her day.

Get a coffee, slip on your pajamas with the bunny-rabbit slippers and allow your mind to wander back in time to a very different place. Listen to Ilona Eibenschütz talk about her lessons with Madame Schumann and how she spent much of her time with Brahms during the last decade of his life.

Listen to what de Lara has to say about Madame Schumann's technique. On the one hand it isn't right to make a passage easy with fingering, on the other hand she seems to be saying that it is okay to divide a passage between the hands in order to make it easy.

|

| Adelina de Lara |

She was educated at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt under Iwan Knorr, and studied piano with Fanny Davies and Clara Schumann, whose work she championed for most of her life. She was close friends with Johannes Brahms through her studies. As an adult, Adelina de Lara performed in public for the first time following her studies in 1891 and continued for over seventy years, making her final appearance on 15 June 1954 at the Wigmore Hall London. She made many recordings for the BBC and appeared on BBC Television on her 82nd birthday.

During World War II she played for Dame Myra Hess at the National Gallery and later in life, Sir Adrian Boult. In 1951 Adelina was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE). The late Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother was both an admirer and a friend and sent good wishes for concerts on many occasions. She also worked as a teacher, her students including Eileen Joyce and many other distinguished pianists. She composed many pieces which have included ballads, song cycles and many for piano including two concertos. There were also two suites for strings, including 'In The Forest', which was performed in 2005, in Gloucester Cathedral by the Gloucester Academy of Music.

Adelina de Lara's autobiography entitled Finale was published in 1955 and she died at the age of 89 in Woking, Surrey on 25 November 1961.

Ilona Eibenschütz, piano

Recorded probably in the 50s.

|

| Ilona Eibenschutz |

From the YouTube notes:

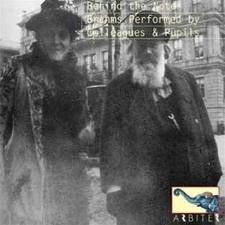

Ilona Eibenschütz (May 8, 1872 in Budapest, Hungary - May 21, 1967 in London, England) was a Hungarian Jewish pianist from Budapest. She received her first instruction in music from her cousin Albert Eibenschütz. At the age of five, Franz Liszt is said to have played at a concert with her (other sources say she played a Duet with Liszt when she was six years old). She later studied with Carl Marek, and from 1878 to 1885 at the Leipzig Conservatory under Hans Schmitt, and then, from 1885 to 1890, with Clara Schumann in Frankfurt. There she met Johannes Brahms in 1886, and she knew him until his death in 1897. She heard him play his own music on various occasions, and in 1926, she wrote (as Mrs. Carl Derenburg) for The Musical Times, "[Brahms] played as if he were improvising, with heart and soul, sometimes humming to himself, forgetting everything around him. His playing was altogether grand and noble, like his compositions." In the summer of 1893, Brahms privately premiered his piano pieces, op. 118 and op. 119, to Eibenschütz. She later wrote, "It was of course the most wonderful thing for me to hear these pieces as nobody yet knew anything about them. I was the first to whom he played them." Her teacher Clara Schumann (1819-1896) was Brahms's closest personal and musical friend, but expressed reservations privately to Brahms

|

| Ilona Eibenschütz with Brahms |

about Eibenschütz's playing, writing to Brahms on 1 February 1894 that "she goes too quickly over everything." (The translation is by Jerrold Northrup Moore in his booklet notes to the Pearl CD, "Pupils of Clara Schumann" - Pearl CDS 99049 - which includes recordings of Eibenschütz.) Following her education, she undertook a successful performing career that led her throughout Europe. She married Carl Derenburg in 1902 and retired from the stage, living the rest of her life quietly in London. She died there on May 21, 1967.

Fanny Davies (1861-1934)

After her studies with Clara Schumann ended, (she had previously been a pupil of Carl Reinecke), Fanny Davies (1861-1934) became one of the most celebrated of English pianists. She gave the first performances in England of Brahms Klavierstucke, Op 116 and 117. And of course, Davies carried on the style and tradition of the performance of Schumann's piano music that she had learned from the composer's widow, Clara.

At the age of 67, Davies made her first recording in 1928 performing the Schumann Piano Concerto. The following year she recorded Schumann's Davidsbundlertanze, Op 6. In December of 1930, Davies made her last released recording of the same composer's Kinderszenen, Op. 15. She also recorded that same month Schumann's Fantasiestucke, Op 12, Romanze in F sharp, Op 28, No. 2 and the Study in canon form Op. 56, No 5. Unfortunately, none of these have been published and may have been lost.

Carl Friedberg

Carl Friedberg plays Schumann "Symphonic Etudes"

From Marston liner notes:

Carl Friedberg (1872-1955)

was a leading 20th-century representative of the Brahms/Schumann pianistic tradition. During his teens, Friedberg enjoyed regular lessons from Clara Schumann as well as the friendship of Johannes Brahms, who coached the young Friedberg in the interpretation of his piano works. Friedberg performed occasional concerts but made no commercial recordings until two years before his death. The only Friedberg recording has long been a prime collector’s item. The entire contents of that disc, taken from the original master tapes, may now be heard on this two-CD Marston release, together with additional works from the same sessions and live performances from Friedberg’s 1949 and 1951 Juilliard recitals. The repertoire includes music of Schumann, Brahms, Beethoven, Chopin, Mozart, and Mendelssohn as well as several improvisations by Friedberg himself. Friedberg was a teacher at the earliest incarnation of the Juilliard School.