My student thought that a trill in Bach had to consist of an even number of notes. He thought it should be duple and that triple was not correct. This gave me pause, as it had never come up before. Here is my rule: Like all ornaments indicated with a symbol, the trill must be given a place in time. Yes? The composer doesn't tell us how many notes or what rhythm they should have. Sometimes it isn't even clear exactly what pitches to play. So, our

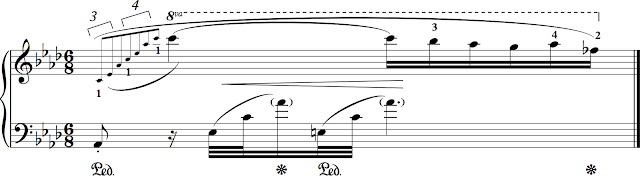

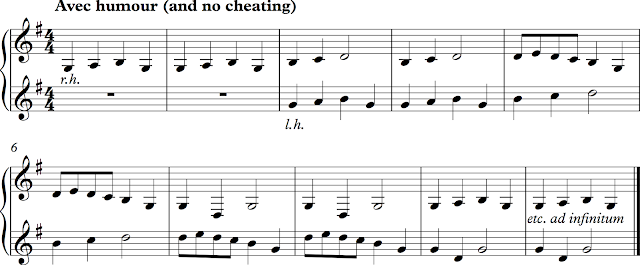

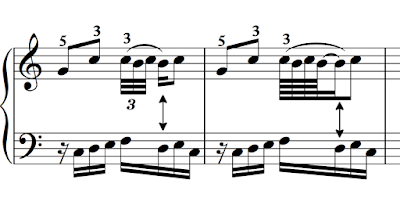

My student thought that a trill in Bach had to consist of an even number of notes. He thought it should be duple and that triple was not correct. This gave me pause, as it had never come up before. Here is my rule: Like all ornaments indicated with a symbol, the trill must be given a place in time. Yes? The composer doesn't tell us how many notes or what rhythm they should have. Sometimes it isn't even clear exactly what pitches to play. So, our I play the trills as indicated in the first example, which is in a slightly faster tempo. The second example is, of course, also possible in a somewhat slower tempo. The main objective is clarity and expressive logic. An ornament should never sound as if someone just pushed you in the back.

I play the trills as indicated in the first example, which is in a slightly faster tempo. The second example is, of course, also possible in a somewhat slower tempo. The main objective is clarity and expressive logic. An ornament should never sound as if someone just pushed you in the back. |

| Two ways to play the trill. |

For more on this topic, see Stannard, Neil, Demystifying Bach at the Piano: Problem Solving in the Inventions and Sinfonias, CreateSpace, 2016.