|

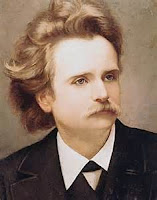

| Edvard Grieg |

I offer this post here now as a reminder to myself, well, all of us, that nothing should ever be assumed. On the one hand it's great to give the benefit of the doubt and let students explore on their own to see what they come up with. Sometimes, though, a simple word in advance can save time and effort. Sigh. But I know this. Really.

A young student brought in the cadenza to Grieg's concerto (1868), proudly showing that he had carefully worked out the complex rhythms at the In Tempo Primo, where Grieg demands we play seven notes in the left hand against eight notes in the right hand. Not really. The composer is only kidding. It's a shimmering effect Grieg wants, not a rhythmic tour de force. As evidence of this, notice the admonition to play piu facile. Legend has it that Grieg was called the "Chopin of the North" by the great pianist-conductor Hans Von Bulow, all the more reason to take a poetic approach here.

|

| Grieg Concerto Cadenza as Written |

This student had indeed worked out a sort of alternating hand version of this passage, but he complained, understandably, that it "wouldn't go." I gave him my standard explanation that the score gives us the sound of the passage, not the feel of it in our hands. So, I offered the following practical revision. Notice the slight adjustment in the right hand thirty-seconds, one instance in which I agree with pianist-editor Percy Grainger. The effect of the right hand tremolo with the left hand arpeggios creates a vague curtain of sound, a musical impression of light filtered through mist. It is not meant to be clearly articulated.

|

| Grieg Concerto Cadenza as Played |

After a bit of searching through my score library, I found my copy of the concerto almost where it should have been. It was dated, well, never mind the date. I was fourteen, about the same age as this student. I showed him my very large and very deliberate self-reminder scrawled across the top of the page in deeply indented graphite: S L O W P R A C T I C E. My teacher probably made me put it there. It's good advice.