A student complains that after much effort he's

|

| Claude Debussy 1862-1918 |

|

| Gustav Klimt, Art Nouveau |

|

| Arabesque No. 1, MM 31-38 Claude Debussy |

|

| Art Nouveau in Architecture |

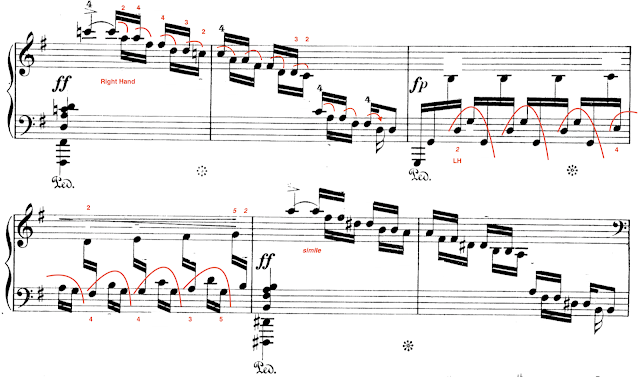

The solution to this problem comes under the heading "The score tells us how the music sounds, not how it feels in our hands." It's a grouping issue primarily, with a hint of shaping. Begin each group with the thumb and shape a little under to the chord, which will be a little higher. Get off of the chord in order to land back on the next thumb, which helps send the hand to the next chord. The pedal will disguise any unwanted disconnect. For an enhanced illusion of legato, voice the chords firmly to the top. (Click the image to enlarge.)

|

| Debussy Arabesque No. 1 MM 31-38 with technical suggestions |

I hope this helps.