|

| C.P.E. Bach 1714-1788 |

Playing the Piano is Easy and Doesn't Hurt! Learn how to solve technical problems in Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin and all the other composers you want to play. Reconsider whether to spend time on exercises and etudes or music. Discover ways to avoid discomfort and injury and at the same time increase learning efficiency. How are fast octaves managed without strain? How are leaps achieved without seeming to move? And listen to great pianists of the past.

“Music is a moral law. It gives a soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, a charm to sadness, and life to everything. It is the essence of order, and leads to all that is good, just and beautiful, of which it is the invisible, but nevertheless dazzling, passionate, and eternal form.” Plato

Solfeggietto by C.P.E. Bach: A question of Fingering

Grieg's Holberg Suite: Fingering

A student writes: "I have a problem playing the

alternating-hands fingering in Grieg's "Holberg

Suite," op. 40, first movement. I find the alternating right and left hands so difficult that it makes me wonder if the design is to limit the tempo these sixteenth notes can go, or insure they will be played clearly and cleanly? I can go faster just playing the entire passages in the right hand!"

I respond that I'm embarrassed to admit I haven't explored Grieg's piano music much except for the concerto and the transcription of "Notturno." Originally known as "From Holberg's Time," the suite consists of dances in an 18th century style. I know the "Holberg Suite" from its string orchestra version, which is very compelling. But, apparently, the suite was originally for piano solo. It was Grieg's contribution to the two-hundredth anniversary celebration of the 17th -18th century playwright, Ludvig Holberg.

The question of fighting with an uncomfortable fingering in the score when an easier one is available reminds me of something someone once said. Oh, wait. I said it: "The score tells us how the music sounds, not how it should feel in our hands." So regardless of the fact that the uncomfortable fingering might be designed to slow us down or force us to play more cleanly, take the easier fingering. You can still decide on the tempo and clarity with a more agreeable fingering. So this student's instinct is correct, play the passage in the right hand. It is not necessary to alternate hands.

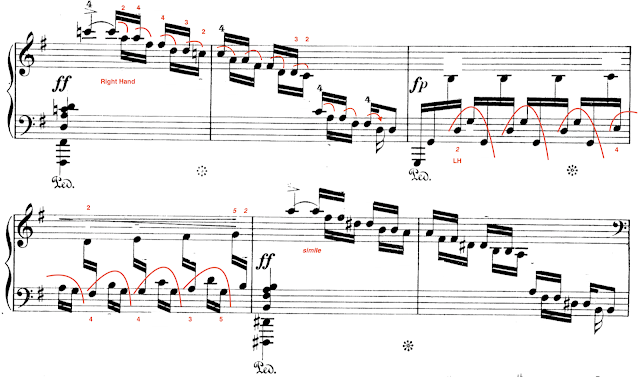

Here is my suggested fingering and redivision between the hands: (Click the image to enlarge.)

alternating-hands fingering in Grieg's "Holberg

|

| Ludvig Holberg 1684 –1754 |

|

| Edvard Grieg 1843-1907 |

The question of fighting with an uncomfortable fingering in the score when an easier one is available reminds me of something someone once said. Oh, wait. I said it: "The score tells us how the music sounds, not how it should feel in our hands." So regardless of the fact that the uncomfortable fingering might be designed to slow us down or force us to play more cleanly, take the easier fingering. You can still decide on the tempo and clarity with a more agreeable fingering. So this student's instinct is correct, play the passage in the right hand. It is not necessary to alternate hands.

|

| Edvard Grieg, Holberg, Ist Movement |

Pianists have Questions: Don't Be Afraid to Ask

When I was a teenage pianist and intimidated by authority, it never occurred to me to ask a question. "What do you mean by 'get after that,'" I should have asked. "Your playing is dishonest" should have raised my hackles and brought about at least a raised eyebrow.

When I was a teenage pianist and intimidated by authority, it never occurred to me to ask a question. "What do you mean by 'get after that,'" I should have asked. "Your playing is dishonest" should have raised my hackles and brought about at least a raised eyebrow. I had the privilege of studying under some great artist-teachers who had been child prodigies. They were doers rather than sayers, so probably didn't know very much about how they did it, technically speaking. One of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, Vladimir Horowitz, when

|

| Vladimir Horowitz |

Now I know how to "get after" a technical problem and how to be "honest" technically. So, if any of you, dear readers, have a question, fire away and I'll try to help. When I first started this blog, I made a similar offer, but in the meantime the comments link broke. Sigh. I'm happy to report that it is repaired. If you would like to ask something, please be as specific as possible and I'll post a reply as soon as I can.

Now I know how to "get after" a technical problem and how to be "honest" technically. So, if any of you, dear readers, have a question, fire away and I'll try to help. When I first started this blog, I made a similar offer, but in the meantime the comments link broke. Sigh. I'm happy to report that it is repaired. If you would like to ask something, please be as specific as possible and I'll post a reply as soon as I can. Demystifying Bach: Introduction Continued

The Technique

In these pages we consider the techniques, the how-tos, of coordinating more than one musical line. We learn to apply principles of grouping notes together and shaping lines in certain ways for technical ease. We consider possible fingerings,

sometimes more than one, depending on the desired effect. Often, technical solutions coincide with musical objectives. This makes us happy. But when there is a technical problem, we examine it on its own merits. No mindless rote here.

Often in the text I refer to rotation. This is shorthand for forearm rotation, of which there are two types, single and double. The terminology is not important. Suffice it to say that single rotation is the sort applied

when changing direction with each note, as in a trill or an Alberti figure. Double rotation occurs when the finger moves both to and from notes that move in the same direction, as in a scale.

When the hands work together rotationally there are four applications: parallel left, parallel right, opposite inward and opposite outward. Parallel right means that the two hands both open to the right, then rotate back leftward into the note. Parallel left is the reverse. Opposite inward means that the hands both open with their backs toward each other. Opposite outward is the reverse, the palms are facing each other. I know it sounds confusing, but the applications are quite simple. Not only that, these are natural movements that the body will accept without complaint.

Occasionally a technical solution will require what I call a

walking hand or walking arm. This is nothing more than a combination of rotation with a lateral movement and slight opening of the hand. Remember, the hand can be open without feeling stretched to an extreme.

Sometimes I use the word pluck to indicate a springing action away from a note. This is akin to what happens when bending the knees to create thrust from a diving board. I don’t necessarily mean that the note is staccato. This movement is always tiny and propels the hand laterally, not vertically. In a leap, this plucking action achieves the distance to the point over the desired landing spot. Gravity and rotation then help create the note.

Sometimes I use the word pluck to indicate a springing action away from a note. This is akin to what happens when bending the knees to create thrust from a diving board. I don’t necessarily mean that the note is staccato. This movement is always tiny and propels the hand laterally, not vertically. In a leap, this plucking action achieves the distance to the point over the desired landing spot. Gravity and rotation then help create the note.

If a passage of counterpoint feels uncoordinated, it is very

likely that one hand is trying to do what the other is doing. The best way to solve these issues is to first examine the type of forearm rotation required in each hand separately. Then, feel them together. The hands can be a little stupid sometimes. They need to be shown what the mind knows.

(For a video demonstration of the aforementioned, click on the iDemos tab at the top of the page and select Inventions and Sinfonias.)

To be continued:

In these pages we consider the techniques, the how-tos, of coordinating more than one musical line. We learn to apply principles of grouping notes together and shaping lines in certain ways for technical ease. We consider possible fingerings,

sometimes more than one, depending on the desired effect. Often, technical solutions coincide with musical objectives. This makes us happy. But when there is a technical problem, we examine it on its own merits. No mindless rote here.

Often in the text I refer to rotation. This is shorthand for forearm rotation, of which there are two types, single and double. The terminology is not important. Suffice it to say that single rotation is the sort applied

when changing direction with each note, as in a trill or an Alberti figure. Double rotation occurs when the finger moves both to and from notes that move in the same direction, as in a scale.

When the hands work together rotationally there are four applications: parallel left, parallel right, opposite inward and opposite outward. Parallel right means that the two hands both open to the right, then rotate back leftward into the note. Parallel left is the reverse. Opposite inward means that the hands both open with their backs toward each other. Opposite outward is the reverse, the palms are facing each other. I know it sounds confusing, but the applications are quite simple. Not only that, these are natural movements that the body will accept without complaint.

Occasionally a technical solution will require what I call a

walking hand or walking arm. This is nothing more than a combination of rotation with a lateral movement and slight opening of the hand. Remember, the hand can be open without feeling stretched to an extreme.

Sometimes I use the word pluck to indicate a springing action away from a note. This is akin to what happens when bending the knees to create thrust from a diving board. I don’t necessarily mean that the note is staccato. This movement is always tiny and propels the hand laterally, not vertically. In a leap, this plucking action achieves the distance to the point over the desired landing spot. Gravity and rotation then help create the note.

Sometimes I use the word pluck to indicate a springing action away from a note. This is akin to what happens when bending the knees to create thrust from a diving board. I don’t necessarily mean that the note is staccato. This movement is always tiny and propels the hand laterally, not vertically. In a leap, this plucking action achieves the distance to the point over the desired landing spot. Gravity and rotation then help create the note.If a passage of counterpoint feels uncoordinated, it is very

likely that one hand is trying to do what the other is doing. The best way to solve these issues is to first examine the type of forearm rotation required in each hand separately. Then, feel them together. The hands can be a little stupid sometimes. They need to be shown what the mind knows.

(For a video demonstration of the aforementioned, click on the iDemos tab at the top of the page and select Inventions and Sinfonias.)

To be continued:

Demystifying Bach At the Piano: Introduction

INTRODUCTION

We pianists are both blessed and cursed. On the one hand we glory in the totality of musical possibility, controlling as we do

We pianists are both blessed and cursed. On the one hand we glory in the totality of musical possibility, controlling as we do

massive sonorities. We can be the entire string quartet, the singer and accompanist, the full orchestra. We learn at an early age to be horizontalists, the producers of a musical line. We learn that music exists in time and travels logically from point A to points farther along an horizontal continuum. This is all good.

On the other hand, when confronted with competing horizontal lines, we are called upon to rethink our predilection for spinning a single line beautifully to the right. Students suffer the shock of having to abandon preconceived notions of technique, at least for the amount of time it takes to organize more than one line traveling together at the same time along the same continuum. Yes, and to some this may seem sacrilege, but we must think more vertically.

On the other hand, when confronted with competing horizontal lines, we are called upon to rethink our predilection for spinning a single line beautifully to the right. Students suffer the shock of having to abandon preconceived notions of technique, at least for the amount of time it takes to organize more than one line traveling together at the same time along the same continuum. Yes, and to some this may seem sacrilege, but we must think more vertically.

Mastering contrapuntal playing at the piano is about physical coordination. What do the two hands feel like at crucial points

where the multiple voices come together vertically? Since the piano is down—we play down into the key—the feeling where voices come together is a combined down. I know, this flies in the face of our notion that music moves laterally.

Bach was a teacher. In his day, teaching was not only about keyboard facility, but included elements of composition and style. In short, Bach taught music. In his preface to the Inventions and Sinfonias, he explains that he has created an “honest method” for the purpose of learning to play “clearly” first two parts, then three

parts. Along the way he hoped the “amateur” would develop, in addition to the ability to handle all the parts well, “good ideas.” He writes that “above all” the player should “achieve a cantabile style in playing and acquire a strong foretaste of composition.”

Let’s talk about cantabile. This is my favorite Bach quote. I raise it whenever I encounter a pianist who attempts a harpsichord facsimile on the modern piano. You know the type of player I mean. This is someone who feels that all Bach playing is detached. (More about articulation later.) Even the great harpsichordist Wanda Landowska declared that her playing was connected, not detached. I understand why some pianists do this. They hope to imitate the quill plucking the strings. In the process they discard the natural reverberation that plucking produces.

We know that Bach favored the clavichord for its ability to

produce nuanced inflections, not unlike a piano, though very much more subtle. The clavichord was an entre nous instrument, its sound intimate and not designed for a modern concert hall. It seems to me Bach had this reference in mind when he wrote that his music should be expressive in the way that singing can be expressive. In the above-referenced preface Bach gives us leave to use the resources of the piano.

So here we have a conundrum. On the one hand we are to play the parts clearly, but at the same time be expressive. No worries. We can separate out the two parts of the puzzle and put them back together again. Bach would be proud.

To be continued...

We pianists are both blessed and cursed. On the one hand we glory in the totality of musical possibility, controlling as we do

We pianists are both blessed and cursed. On the one hand we glory in the totality of musical possibility, controlling as we do massive sonorities. We can be the entire string quartet, the singer and accompanist, the full orchestra. We learn at an early age to be horizontalists, the producers of a musical line. We learn that music exists in time and travels logically from point A to points farther along an horizontal continuum. This is all good.

On the other hand, when confronted with competing horizontal lines, we are called upon to rethink our predilection for spinning a single line beautifully to the right. Students suffer the shock of having to abandon preconceived notions of technique, at least for the amount of time it takes to organize more than one line traveling together at the same time along the same continuum. Yes, and to some this may seem sacrilege, but we must think more vertically.

On the other hand, when confronted with competing horizontal lines, we are called upon to rethink our predilection for spinning a single line beautifully to the right. Students suffer the shock of having to abandon preconceived notions of technique, at least for the amount of time it takes to organize more than one line traveling together at the same time along the same continuum. Yes, and to some this may seem sacrilege, but we must think more vertically. Mastering contrapuntal playing at the piano is about physical coordination. What do the two hands feel like at crucial points

where the multiple voices come together vertically? Since the piano is down—we play down into the key—the feeling where voices come together is a combined down. I know, this flies in the face of our notion that music moves laterally.

Bach was a teacher. In his day, teaching was not only about keyboard facility, but included elements of composition and style. In short, Bach taught music. In his preface to the Inventions and Sinfonias, he explains that he has created an “honest method” for the purpose of learning to play “clearly” first two parts, then three

parts. Along the way he hoped the “amateur” would develop, in addition to the ability to handle all the parts well, “good ideas.” He writes that “above all” the player should “achieve a cantabile style in playing and acquire a strong foretaste of composition.”

Let’s talk about cantabile. This is my favorite Bach quote. I raise it whenever I encounter a pianist who attempts a harpsichord facsimile on the modern piano. You know the type of player I mean. This is someone who feels that all Bach playing is detached. (More about articulation later.) Even the great harpsichordist Wanda Landowska declared that her playing was connected, not detached. I understand why some pianists do this. They hope to imitate the quill plucking the strings. In the process they discard the natural reverberation that plucking produces.

We know that Bach favored the clavichord for its ability to

|

| Clavichord |

So here we have a conundrum. On the one hand we are to play the parts clearly, but at the same time be expressive. No worries. We can separate out the two parts of the puzzle and put them back together again. Bach would be proud.

To be continued...

Chopin's Fourth Ballade: The Tempo is Only Andante

Okay, the tempo is actually andante con moto (moderately slowly but with motion). Even so, it's only that and doesn't change much except for a few authorized slowings down and speedings up. Really. Look at the score.

Okay, the tempo is actually andante con moto (moderately slowly but with motion). Even so, it's only that and doesn't change much except for a few authorized slowings down and speedings up. Really. Look at the score. Coincidental to my restudying of Chopin's F Minor Ballade, the other day I came upon a FaceBook post offering an historical recording of Glenn Gould playing Beethoven's Appassionata, first movement. The eccentric genius plays at about half tempo, what I would call a good practice tempo. The

|

| Glenn Gould |

As I thumb through the pages of Chopin's Ballade, I notice no

|

| Frédéric Chopin |

I make this comparison because the issue is about trying our best as artists, as re-creators, to realize the composer's intentions, keeping in mind that a composer like Chopin, for example, has it over us as a creative genius. Regrettably, I'm not able to declare that any of the pianists I've heard had, like Gould, an educational purpose in mind as they disregarded Chopin's instruction—or anything at all in mind, except perhaps, and I think I'm being generous here, to amaze their listeners.

I'm thinking now of the passage beginning in measure 100, the onset of a development. Yes. Chopin thinks Classically. (Notice the capital 'C'.) This is all the more reason to think of a more consistent (not rigid) tempo. Here the composer writes a tempo. As we all know, this means return to the main tempo—which in this case is after a ritardando—not take a new one. Many pianists take off like a Czerny machine gone mad, but these passages are so much more meaningful than that and take on a remarkable expressiveness when played more or less in tempo—the indicated tempo—and with lyrical intent.

|

| Chopin's F Minor Ballade, MM 100-103 (The 'a' of a tempo is in the previous measure.) |

At the variation beginning in measure 152—yes, we have variations on a theme, another Classical convention—which is also typically played too fast. The melismas should each be allowed to speak for themselves, not pressed together like a glissando.

|

| Chopin's F Minor Ballade, MM 150-155 |

Even the etude-like passage in measure 191 (think 'Ocean' Etude) doesn't need to speed up, though I think Chopin might approve a slight forward tilt. There is no change of tempo indicated in the score. If this passage becomes too climactic, what are we going to do with the coda? The coda, by the way, has no tempo change, either. This is fortunate because it can be sticky to play cleanly, and we do want to hear the new material. (Richter, whom I admire greatly, plays so fast one can't hear anything.)

|

| Chopin's F Minor Ballade, MM 190-193 |

So, aside from a stretto in measure 199 and an accelerando from measure 227 to the end, there are no indications from the composer to make significant tempo changes.

Okay, I hear the "but, but..." Yes, Chopin's music is nothing if not flexible, like his hands, apparently. But we are not talking here about the so-called "tempo rubato", referring to the rhythmic relationship of the hands, which can be "out of phase." We learn

|

| Karol Mikuli |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)