Myra Hess (1890-1965) plays her very famous arrangement of Bach's Chorale "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring." Listen and watch here: Myra Hess

Myra Hess (1890-1965) plays her very famous arrangement of Bach's Chorale "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring." Listen and watch here: Myra Hess

Her favorite anecdote relating to "Jesu, Joy" concerned a British soldier who whistled it on a train during the war.

"Are you interested in Bach?," the soldier was asked by a journalist.

"No," he answered.

"But you are whistling a Bach composition," the newsman insisted.

"That's no Bach," he replied indignantly. "That's Myra Hess."

(From Marian McKenna's "Myra Hess -- A Portrait")

|

| in 1921 |

As an adult, I became aware of her heritage. She had been from the age of twelve a pupil in London of Tobias Matthay and it was under his supervision that she made her professional debut at the age of seventeen with Sir Thomas Beecham in the Beethoven Fourth Concerto at the Royal Albert Hall.

As an adult, I became aware of her heritage. She had been from the age of twelve a pupil in London of Tobias Matthay and it was under his supervision that she made her professional debut at the age of seventeen with Sir Thomas Beecham in the Beethoven Fourth Concerto at the Royal Albert Hall.

Matthay is credited with the observation that the forearm is of primary importance in efficient piano technique. Watch her hands on the keys. One can't always see what's going on underneath the technique, but in her case notice how "closed" her hands are and hear the well-focused sound she produces. Dorothy Taubman was the next to take up Matthay's ideas on forearm rotation and run with them, and it's Taubman's research that informs my own playing, teaching and writing.

|

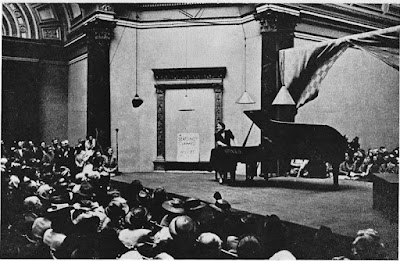

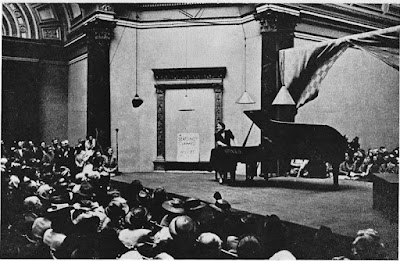

Lunchtime Concert |

In addition to her artistry, Hess is remembered for her bravery and public service during WWII. Because of the nighttime blackouts, she organized nearly 2000 daily

lunchtime concerts that took place during the German blitz. These took place at the national Gallery in Trafalgar Square. During bombing, the concerts moved to a smaller, safer room. The concerts served as an opportunity for emerging artists to perform alongside established artists, including Hess, who took no fees for herself. Nearly one million people attended these events during the six-and-a-half years of the war. She personally appeared in 150 performances.

Her students, the Contiguglia brothers, report the following in an interview: "I want to just say a few more words about turning pages for her because it was really an extraordinary experience. One experience was turning when she did the Mozart E-Flat Concerto K. 271 with the New Haven Symphony, and I remember it was a memorable performance, simply beautiful. It stirred my emotions and made it very difficult to turn, but at the end of the finale she turned to the audience, because they wouldn’t let her leave, and she said ‘you know, the slow movement of this concerto was one of the most beautiful things that Mozart ever wrote, I would like to repeat it’, and so she went and played the slow movement again with the orchestra, and then she turned to me and said ‘that time it worked’.

"She was so human and she seemed to value the impression that her page-turner had from her concert. Of course, I was so moved that I wondered whether I was ever going to be able to turn pages, but I managed. I like to think of Myra Hess as being a sort of platonic ideal. You know, she represented an artistry that all the rest of us aspired to. Of course we never can achieve what she was, but it is an ideal, a platonic ideal, for me; this is the way perfection is.

|

| Official Portrait, National Gallery |

"I remember that the last Carnegie Hall recital that we heard her perform, she did the last three Beethoven sonatas; Opus 109, Opus 110 – one sonata was just more magisterial than the next. When she finished Opus 111, there was total silence in that sold-out house, not one single clap, nobody said anything and nobody made a sound, and finally after an inordinately long time the entire audience rose to its feet, still silently, and then burst out into tumultuous applause. And that’s the effect a Myra Hess recital had, at least on an American audience."If you have time, here's a live radio broadcast from 1946:

Dame Myra Hess & Arturo Toscanini: Beethoven Piano Concerto No.3 (pitch-corrected)

If you have still more time:

Brahms 2nd Concerto, live, Carnegie Hall, 1952, with Bruno Walter

If you would like to hear more, select the "Listen" tab above and scroll down to the Brahms D Minor Concerto with Dimitri Metropolis.