|

| C.P.E. Bach 1714-1788 |

Playing the Piano is Easy and Doesn't Hurt! Learn how to solve technical problems in Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin and all the other composers you want to play. Reconsider whether to spend time on exercises and etudes or music. Discover ways to avoid discomfort and injury and at the same time increase learning efficiency. How are fast octaves managed without strain? How are leaps achieved without seeming to move? And listen to great pianists of the past.

“Music is a moral law. It gives a soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, a charm to sadness, and life to everything. It is the essence of order, and leads to all that is good, just and beautiful, of which it is the invisible, but nevertheless dazzling, passionate, and eternal form.” Plato

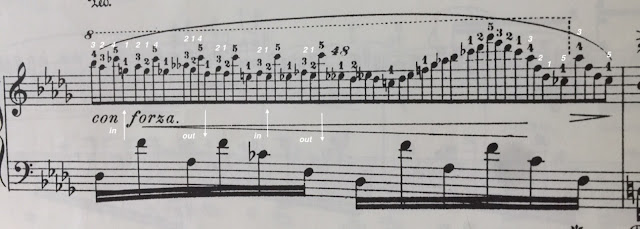

Solfeggietto by CPE Bach: Fingering vs Grouping

Sonatina by Kabelvsky: Coordination Between the Hands

|

| Dimitri Kabalevsky |

My adult student brought this familiar foray into classical style a la the 20th century. He stumbled often, but not always, at the two scale passages, G minor as shown here (Ex. 1), and the same passage on C minor a few measures later. Notice that nothing could be more innocent harmonically: a G melodic minor scale over a first-inversion arpeggio, also G minor:

|

| Kabalevsky Sonatina, Op. 13, No. 1, Third Movement |

Two issues are in play here: the musical objective and the

technical means. I know, I know. What else is new? I point this out because my student fell victim to the musical objective as indicated in the score, trying for a whoosh without feeling the milestones along the way.

Step one is to notice which fingers of each hand are partnered and encourage them to cooperate by feeling a down together. Do this very slowly. (I've indicated these fingerings in Ex. 2.) Feel these pairs first on each eighth. Then, moving on to step two, feel the pairs on each quarter—still very slowly. Then comes the crucial third step: Notice the pair of fingers on the downbeat of measure two. Aha! This is not the beginning of the scale. Feel a secure starting place here. Gradually work up the tempo feeling, though not necessarily hearing, the pulses. Go ahead. Try it. It's fun.

I'm happy to report that my student was able to solve the issues in the lesson. I sent him home, though, having elicited a promise that he will continue to practice along the same lines.

Leaping To and Fro: Rachmaninoff Prelude in G Minor

My colleague in the English department had a framed cartoon on the wall over his desk. A cowboy rushes out of a saloon, the swinging doors flapping. His eyes widened in panic, he runs toward a horse hitched at the trough. The caption reads: "And he ran from the saloon, jumped onto his horse and rode off in all directions."

Okay, okay. I hear the grumbling. This is about grouping. One way to organize groups is to start from the heavier to the lighter. Chord to single note, for example. Then, use the single note as a springboard to land back on the next starting chord. By springboard I mean something like a diving board that propels the hand to the next place, a passive motion that allows the hand to let go for a split second. By using the chord as the organizing factor, the playing mechanism won't feel as if it's going in two directions at the same time. Notice, too, that the left-hand leap is farther than the right, so it will move first.

As I reviewed the video, I noticed I didn't start "in" as I recommended. I felt this as a greater distance than it needs to be. So, do as I say, not as I demonstrate. Also, when leaping to a place directly in front of the torso, lean slightly away, in this case to the left in order to avoid twisting at the wrist.

Arensky Variations Transcribed for Piano Duet

|

| Anton Arensky |

I recently posted information about my transcription of Anton Arensky's "Variations on a Theme of Tchaikovsky." Some piano folks are understandably not very familiar with this Russian composer from the Romantic era, as he did not write extensively for piano. So, here is a recording of the original version for string orchestra:

Listen here: Arensky Variations

Explore here:

Chopin Nocturne in D-flat, Op, 27, No. 2: Pesky Melisma

Rotation

Grouping

Broadening the Musical Experience: Piano Four-hand Transcriptions

|

| Bette Davis |

Every now and then—okay often—I cite a reference with my students that dates me. I've learned, for instance, that film stars from the golden age of Hollywood are no longer in the firmament. Bette Davis (mid-twentieth century movie star) once said "If everyone likes you, you’re not doing it right.” I thought this apropos for students enduring the rigors of competitions. The most celebrated musicians that I grew up revering are at most an echo in some distant galaxy. Arthur Rubinstein was once the go-to pianist for all things Chopin. His training began, after all, in the late nineteenth century.

|

| Arthur Rubinstein |

Sometimes I allude to other instrumental works or opera in order to make a point for students. When these references elicit blank stares, I begin to think there's something missing in the musical education. Hence my present occupation, which, admittedly arose out of an abundance of at-home time in recent months. I have been transcribing significant and engaging works, orchestral and piano, for piano four hands. The hope is that the joy that comes from sharing music with a partner will instill a broader appreciation of other genres and of larger piano works that may lie a bit beyond technically, in the virtuoso realm. These pieces are remarkably easier to play as duets, and in the process of playing them, one begins to unlock some of their mysteries. The Brahms "Handel Variations" is in the works. But available now is the "Variations on a Theme of Tchaikovsky" by Anton Arensky.

|

| Huh? |