It occurred to me at the dawn of our universal shut-in that the Schubert Sonatinas for Piano and Violin needed an incarnation as a string quartet. So, for my pianist readers who are also string players, here is a link to said score. I assume that we shall all be able to safely gather together at some point in the not too distant future. The parts are available individually or in a volume (cheaper) that requires manual separation by means of minor violence:

Playing the Piano is Easy and Doesn't Hurt! Learn how to solve technical problems in Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin and all the other composers you want to play. Reconsider whether to spend time on exercises and etudes or music. Discover ways to avoid discomfort and injury and at the same time increase learning efficiency. How are fast octaves managed without strain? How are leaps achieved without seeming to move? And listen to great pianists of the past.

“Music is a moral law. It gives a soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, a charm to sadness, and life to everything. It is the essence of order, and leads to all that is good, just and beautiful, of which it is the invisible, but nevertheless dazzling, passionate, and eternal form.” Plato

Memorizing Piano Music

A student asks: "Were you taught memorization skills anywhere on your piano journey? What do you think is most important when memorizing music?"

A student asks: "Were you taught memorization skills anywhere on your piano journey? What do you think is most important when memorizing music?"No, none of my teachers taught how to memorize. To them, memorization was a nebulous thing, a topic not to see the light of day.

If there's one "most" important issue, it would have to be the inclusion of all of the memories. I think it's a mistake to rely solely on digital memory, which is what mindless repetition gives us. So when memorizing, I suggest removing as much digital memory as possible as soon as

possible, which will force the engagement of the ear, eye and the most important of these, the intellect, which includes grasping musical intent and structural details such as harmonic vocabulary and form.

When I was a student I memorized by accident, not on purpose. It's important to notice the difference. The former consists mostly of rote

learning, training the digital memory; the latter stresses thought and imagination. I probably noticed more than I realized, having been steeped at the time in intensive music theory studies. I tell students—and myself—to say out loud, "Now I'm going to memorize." They should notice whatever they can—this note is the same as that note one octave higher. Or this passage is in or around the tonic. It isn't necessary to make a formal analysis. I notice beginnings and endings—phrases, periods—and make sure I can start at any of these junctions.

My favorite strategy for testing memory is to first play through a passage excruciatingly slowly. This removes much of the digital memory and reveals weaknesses in the other senses. It also gives time to imagine what comes next so that it can be played on purpose, deliberately and not on auto pilot. Even better, and much harder, is to think through the piece away from the piano, seeing your hands playing on the keys. This reinforces visual and aural memory and also will

reveal problem spots. Certainly, in performance we rely on the automatic responses of motor memory, but without having trained the other senses, too, it's like flying without a net.

Beethoven and the Metronome: An Uneasy Alliance

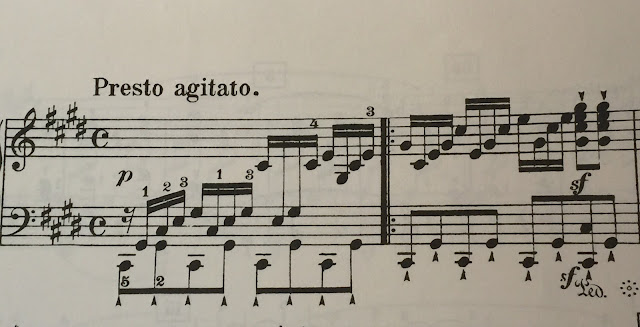

My student forwarded me a link to an originalist pianist who is caught up in a study of Beethoven's intended tempos for the piano sonatas. He argue's that in the final movement of the Moonlight Sonata Czerny's metronome marking (yes, Czerny's) of a half-note equals 92 really means a quarter-note equals 92. He gives as evidence a passage toward the end where thirty-second notes seem to him to require slowing the tempo to one-half. He compares his version with the extravagant pianist, Valentina Lisitsa. It's a stark contrast. His performance at this tempo sounds to me like an andante amiable, not a presto agitato.

|

| Beethoven Op.27, No. 2, 3rd Movmt. |

|

| Beethoven Op. 27, No. 2, 3rd Movmt, MM 62-63 |

point. There has been a great deal of research regarding B's tempos, so I won't burden my comments here with much of that. Definitive conclusions are difficult to come by, anyway. (One good resource is Beethoven on Beethoven: Playing the Piano Music His Way by William S. Newman, pp. 83-120.). We have only Czerny and Moscheles (who differ) for metronome references in the piano sonatas (except Op. 106), the provenance and meaning of which have remained unclear. This has led to considerable confusion. On what are their numbers based, anyway? On Beethoven's performances, which according to contemporary accounts varied considerably?

Though B. set out to add metronome marks to his works retroactively, he didn't get to the piano sonatas. He gave up entirely at the end, leaving the last six string quartets and the last three piano sonatas unmarked, giving rise to the speculation that he lost faith in the usefulness of the metronome. (There is quite a bit of back and forth on this in letters to publishers and colleagues.)

This is not really this pianist's point, though. In my performances, I take more seriously the composers written instructions regarding a work's desired affect. In this case Presto agitato is the main clue. This pianist's choice of tempo achieves neither. And it should be mentioned that the Op. 27, No. 2, was written for the composer to perform at a time when his reputation was that of a virtuoso.

Also, the comment regarding Lisitsa's

|

| Valentina Lisitsa |

You'll have to forgive me if I keep returning

|

| Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach |

Great Pianists of the Past: Food for Thought

I write to call attention to the "Listen" tab above. Do give it a try, as it is a secret door into the past where keyboard giants once roamed the concert halls of the world. These artists were steeped in Romantic traditions now nearly lost to us. They touched the hems of some of the many composers we idolize today.

I write to call attention to the "Listen" tab above. Do give it a try, as it is a secret door into the past where keyboard giants once roamed the concert halls of the world. These artists were steeped in Romantic traditions now nearly lost to us. They touched the hems of some of the many composers we idolize today.Immense. Harrowing. Exhilarating.

I've discovered a new pianist, new to me, that is. He is the epitome of the thoughtful artist responding to the world by which he is surrounded. Beethoven is his meat and the piano his heart. Have a look/listen: Igor Levin on Beethoven.

On difficulty Memorizing Music

REPOST

A mother, concerned about her 14-year-old son’s difficulty memorizing music, writes: “Do professional performers have serious problems memorizing pieces, so that it takes [them] much, much longer than average to memorize even using all the standard techniques (repetition, memory stations, practicing away from the keyboard, counting/humming the piece, identifying patterns, etc.)? If so, did it have a negative impact on your studies at conservatory or college? Did you fail to get the instruction on other aspects of the pieces? Did you ever get a pass on memorizing?”

Well, there is no "average" study time when it comes to learning music. The audience doesn't care how long it took to learn the piece, just that it sounds good. Many artists will have a piece in their hands for a year or more before performing it in public. But this mother is really talking about being locked into a student’s situation, bounded by semesters and exams.

My personal experience is that I can memorize rather quickly, largely, I think, because I learned early on to read well. I am reading oriented, so I had to learn techniques for memorizing, which came more easily because I understand quickly what I am looking at. This understanding is the result, too, of years of experience studying and performing many types of music. (Some students are more aurally oriented and find it difficult to read. These students, I find, often present an approximation of the score when memorizing, i.e., incorrect inversions of chords or missing notes. A few are adept at both reading and playing by ear. We try to love these people anyway.) Most of the time in lessons I used the score. This did not have an impact on my studies, as I always had something prepared to play even if not memorized, or better still, I had questions about problem spots.

For me, the primary expenditure of time is in proving to myself that I really know the piece. In this regard, the best technique I know is to play the piece eliminating as much digital memory as possible. I use two devices: 1) I play excruciatingly slowly, placing fingers deliberately, thoughtfully, not automatically as we do in performance; 2) This one is harder. I play the piece in my mind, visualizing my hands on the keys (not looking at the score in my mind). These devices force us to use all the other types of memory, eliminating most of the digital memory. They are both excellent ways of uncovering shaky spots, spots that may only have been in the fingers.

A side note about the power of device 2: I once was waiting my turn to play Davidsbündlertänze in a master class, a piece I had performed often. I was so confident that I hadn't brought the score with me. As I waited outside, I went through certain passages in my mind, visualizing my fingers on the keys. Alas, I came to a spot where I couldn't continue. I could leap over the spot, but couldn't for the life of me find the correct notes in my mind. So, I imagined what it must have been and played it that way in class. Afterward, I checked the score and found that what I played in class was something I made up in my mind. It took precedence over all of the previous muscle training, mostly likely because it was fresh.

Here’s another thought: As this student gets a bit more experience, a few more pieces memorized and more comfortable with the methods that work for him, I suspect the process will begin to move more quickly. Again, I wouldn't limit his performance opportunities just because of memory issues (except where statutory, which is not in real life). Unless there's some disability, what the mother describes sounds to me as if there's something missing in her son’s understanding of the music. And of course, contrapuntal music is more difficult to memorize.

The late Peter Serkin began his performing career reading from the score and that was 50 years ago. I heard Lang Lang play a concerto with the Los Angeles Philharmonic with the score. Cellist Lynn Harrell played a concerto with the score. Pressler played a Mozart concerto with the score. Admittedly, getting started through the usual channels using the score will be a challenge but if there are other compelling reasons why he should perform, then I say he should try for it. As for preparing for college level lessons, he can memorize pieces before he takes them in to class. One writer suggested that the only option for this student is to become a collaborative pianist. There's nothing wrong with becoming a collaborative pianist, but he should only do it if that’s his calling, not by default.

To this day I'm not convinced that all of the time and nervous energy expended on performing from memory is worth the trouble. It continues to be the standard for schools and competitions, but is gradually losing some importance in the professional world. Some personalities seem more at home playing without the score, but it seems to me that music making is not primarily about performing without a net. In the 19th century it was considered presumptuous to play another person’s music without the score. Maybe its time for performers to become a bit more humble and make the concert more about the music and less about themselves.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)