A mother, concerned about her 14-year-old son’s difficulty memorizing music, writes: “Do professional performers have serious problems memorizing pieces, so that it takes [them] much, much longer than average to memorize even using all the standard techniques (repetition, memory stations, practicing away from the keyboard, counting/humming the piece, identifying patterns, etc.)? If so, did it have a negative impact on your studies at conservatory or college? Did you fail to get the instruction on other aspects of the pieces? Did you ever get a pass on memorizing?”

Well, there is no "average" study time when it comes to learning music. The audience doesn't care how long it took to learn the piece, just that it sounds good. Many artists will have a piece in their hands for a year or more before performing it in public. But this mother is really talking about being locked into a student’s situation, bounded by semesters and exams.

My personal experience is that I can memorize rather quickly, largely, I think, because I learned early on to read well. I am reading oriented, so I had to learn techniques for memorizing, which came more easily because I understand quickly what I am looking at. This understanding is the result, too, of years of experience studying and performing many types of music. (Some students are more aurally oriented and find it difficult to read. These students, I find, often present an approximation of the score when memorizing, i.e., incorrect inversions of chords or missing notes. A few are adept at both reading and playing by ear. We try to love these people anyway.) Most of the time in lessons I used the score. This did not have an impact on my studies, as I always had something prepared to play even if not memorized, or better still, I had questions about problem spots.

For me, the primary expenditure of time is in proving to myself that I really know the piece. In this regard, the best technique I know is to play the piece eliminating as much digital memory as possible. I use two devices: 1) I play excruciatingly slowly, placing fingers deliberately, thoughtfully, not automatically as we do in performance; 2) This one is harder. I play the piece in my mind, visualizing my hands on the keys (not looking at the score in my mind). These devices force us to use all the other types of memory, eliminating most of the digital memory. They are both excellent ways of uncovering shaky spots, spots that may only have been in the fingers.

A side note about the power of device 2: I once was waiting my turn to play Davidsbündlertänze in a master class, a piece I had performed often. I was so confident that I hadn't brought the score with me. As I waited outside, I went through certain passages in my mind, visualizing my fingers on the keys. Alas, I came to a spot where I couldn't continue. I could leap over the spot, but couldn't for the life of me find the correct notes in my mind. So, I imagined what it must have been and played it that way in class. Afterward, I checked the score and found that what I played in class was something I made up in my mind. It took precedence over all of the previous muscle training, mostly likely because it was fresh.

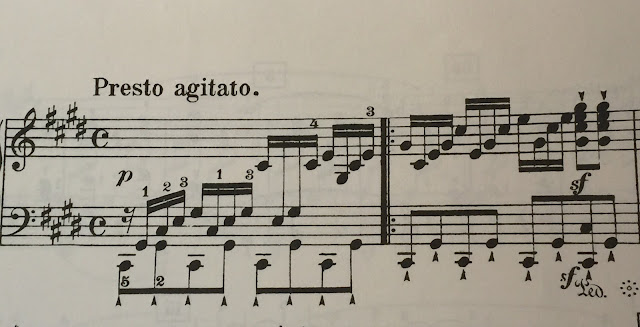

Here’s another thought: As this student gets a bit more experience, a few more pieces memorized and more comfortable with the methods that work for him, I suspect the process will begin to move more quickly. Again, I wouldn't limit his performance opportunities just because of memory issues (except where statutory, which is not in real life). Unless there's some disability, what the mother describes sounds to me as if there's something missing in her son’s understanding of the music. And of course, contrapuntal music is more difficult to memorize.

The late Peter Serkin began his performing career reading from the score and that was 50 years ago. I heard Lang Lang play a concerto with the Los Angeles Philharmonic with the score. Cellist Lynn Harrell played a concerto with the score. Pressler played a Mozart concerto with the score. Admittedly, getting started through the usual channels using the score will be a challenge but if there are other compelling reasons why he should perform, then I say he should try for it. As for preparing for college level lessons, he can memorize pieces before he takes them in to class. One writer suggested that the only option for this student is to become a collaborative pianist. There's nothing wrong with becoming a collaborative pianist, but he should only do it if that’s his calling, not by default.

To this day I'm not convinced that all of the time and nervous energy expended on performing from memory is worth the trouble. It continues to be the standard for schools and competitions, but is gradually losing some importance in the professional world. Some personalities seem more at home playing without the score, but it seems to me that music making is not primarily about performing without a net. In the 19th century it was considered presumptuous to play another person’s music without the score. Maybe its time for performers to become a bit more humble and make the concert more about the music and less about themselves.