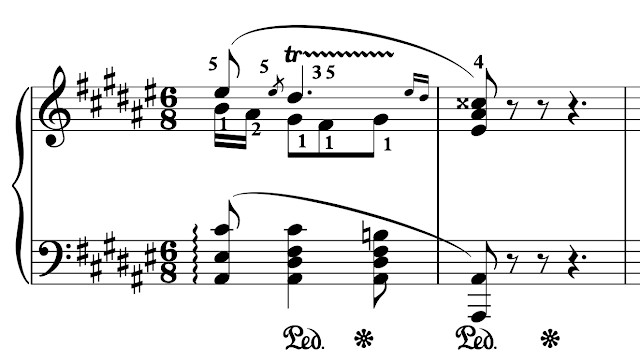

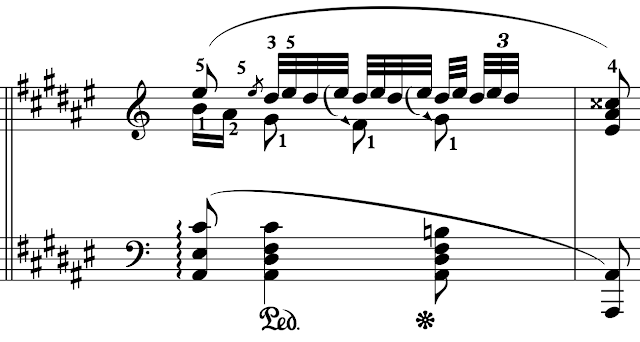

A pianist writes: "I was wondering if you could

offer any suggestions for how to approach the following right hand passage in the F major ballade, particularly the lower line. I don’t see another fingering option besides 32-51. The thumb and fifth finger are so different in length that I can’t get them to sound their notes simultaneously, and I feel like I am sort of stabbing at the B natural and A with an independent motion of my thumb. At speed, it doesn’t work at all."

Since I can't see exactly what she's doing, it's

hard to give a precise diagnosis. However, there are certain issues that are common to this sort of passage that she might want to consider. The first three bars apparently work satisfactorily. One way to start is to try to figure out what is different about the first three bars and the subsequent bars. Yes. Instead of relatively small intervals in close proximity, we now have larger intervals making the distance between the top notes farther.

Since the passage is directly in front of the torso, try leaning slightly to the left in order to avoid twisting and feeling constrained. Remember, too,

that the thumb likes to play in the direction of in. Play slightly in the direction of in for the chord with the thumb and five (shorter fingers) and slightly out again for the longer fingers. These are tiny gestures.

This shaping may solve the problem for her. If not, she can try adding grouping from the wider interval to the smaller one. It's a little like a series of two-note slurs, but very close to the keys and virtually imperceptible. By thinking of starting from the larger interval, you give yourself a nano-split-second of time to get to it from the interval of a fourth without stretching.

.

|

| F. Chopin 1810-1849 |

|

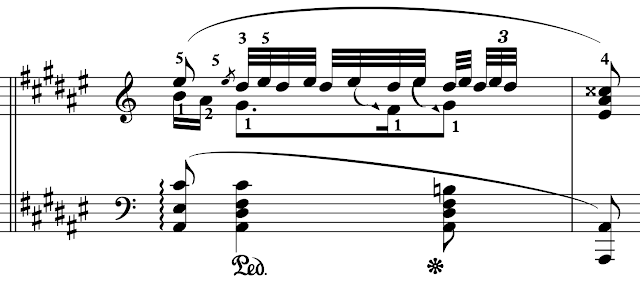

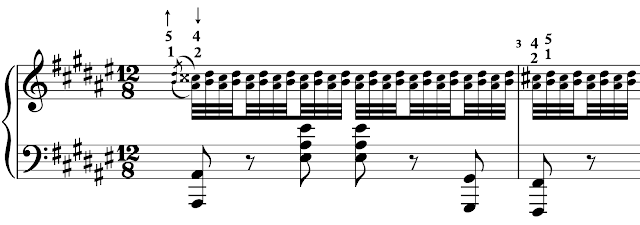

| Chopin F major Ballade Excerpt |

Since I can't see exactly what she's doing, it's

hard to give a precise diagnosis. However, there are certain issues that are common to this sort of passage that she might want to consider. The first three bars apparently work satisfactorily. One way to start is to try to figure out what is different about the first three bars and the subsequent bars. Yes. Instead of relatively small intervals in close proximity, we now have larger intervals making the distance between the top notes farther.

Since the passage is directly in front of the torso, try leaning slightly to the left in order to avoid twisting and feeling constrained. Remember, too,

that the thumb likes to play in the direction of in. Play slightly in the direction of in for the chord with the thumb and five (shorter fingers) and slightly out again for the longer fingers. These are tiny gestures.

This shaping may solve the problem for her. If not, she can try adding grouping from the wider interval to the smaller one. It's a little like a series of two-note slurs, but very close to the keys and virtually imperceptible. By thinking of starting from the larger interval, you give yourself a nano-split-second of time to get to it from the interval of a fourth without stretching.

.