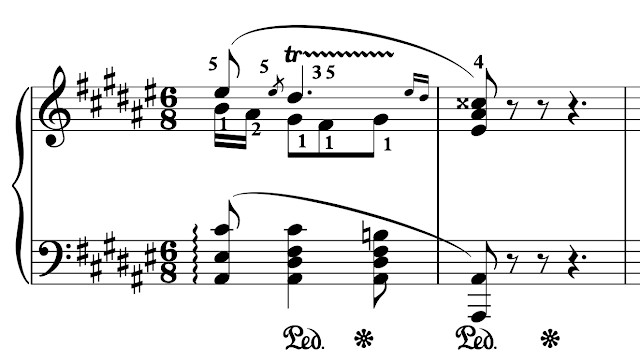

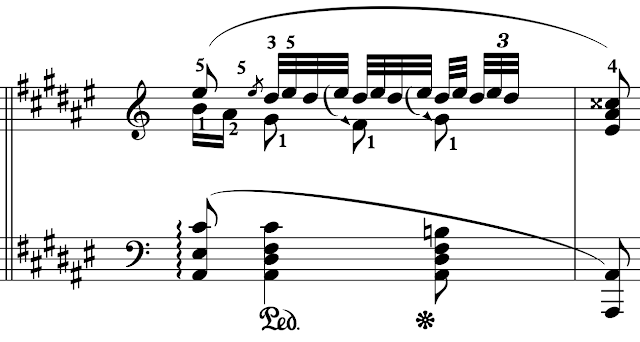

My student asked for advice on playing the orchestra part to the Grieg concerto so that he could accompany several of his students. He showed me certain tutti passages that presented technical problems, which we solved. But we both

agreed that his main issue was that the notes weren't learned. I know. Bummer. Just because you can play the solo part doesn't necessarily mean you have the accompaniment in your fingers. When sight-reading is not your forte, there's no way around learning the notes.

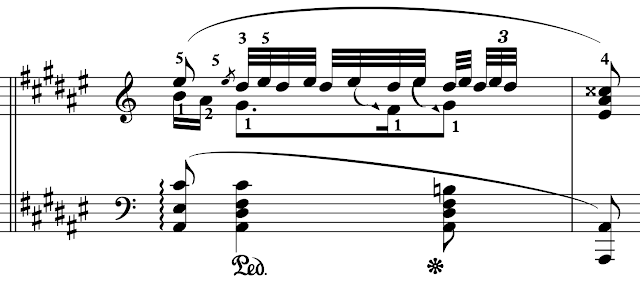

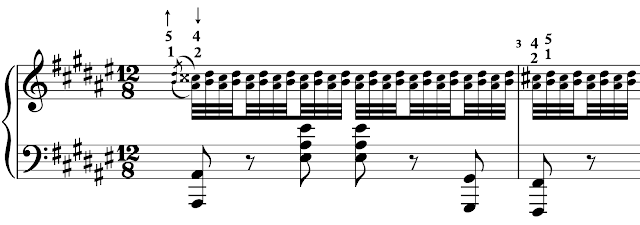

Still, other considerations arose. An orchestral reduction is just one editor's opinion as to what

notes to include, even if that reduction is by the composer himself, it isn't necessary, especially for rehearsal, to be locked into those particular notes. So, pick and choose what to play. My suggestions are these:

Cut tutti passages (unless the soloist really wants to feel a completeness). This will save note learning time. Play a few measures before the solo entry to give the soloist a running start.

Keep a steady tempo under the soloist, allowing his/her rubato to play off of your regularity. This is the most important. The second piano in this situation is both conductor and orchestra. Breathe with the soloist without disturbing the pulse. The orchestra is not allowed to adjust the tempo in order to search for the correct notes.

Keep a steady tempo under the soloist, allowing his/her rubato to play off of your regularity. This is the most important. The second piano in this situation is both conductor and orchestra. Breathe with the soloist without disturbing the pulse. The orchestra is not allowed to adjust the tempo in order to search for the correct notes.

Play with sufficient sound so that the soloist feels supported.

Listen.

agreed that his main issue was that the notes weren't learned. I know. Bummer. Just because you can play the solo part doesn't necessarily mean you have the accompaniment in your fingers. When sight-reading is not your forte, there's no way around learning the notes.

Still, other considerations arose. An orchestral reduction is just one editor's opinion as to what

notes to include, even if that reduction is by the composer himself, it isn't necessary, especially for rehearsal, to be locked into those particular notes. So, pick and choose what to play. My suggestions are these:

Cut tutti passages (unless the soloist really wants to feel a completeness). This will save note learning time. Play a few measures before the solo entry to give the soloist a running start.

Keep a steady tempo under the soloist, allowing his/her rubato to play off of your regularity. This is the most important. The second piano in this situation is both conductor and orchestra. Breathe with the soloist without disturbing the pulse. The orchestra is not allowed to adjust the tempo in order to search for the correct notes.

Keep a steady tempo under the soloist, allowing his/her rubato to play off of your regularity. This is the most important. The second piano in this situation is both conductor and orchestra. Breathe with the soloist without disturbing the pulse. The orchestra is not allowed to adjust the tempo in order to search for the correct notes.

Play with sufficient sound so that the soloist feels supported.

Listen.