A student inquires about fingering choices in

|

| Beethoven 1770-1827 |

the third movement of Beethoven's Sonata Op. 31, No. 2, the so-called "Tempest" (composed 1801-02). Of course Beethoven did not attach that name to it. When asked for interpretive hints by Schindler, Beethoven's friend and helper, the master apparently referred him to Shakespeare's play, The Tempest. No doubt Beethoven had in mind the first scene of the play, which takes place at sea during a storm.

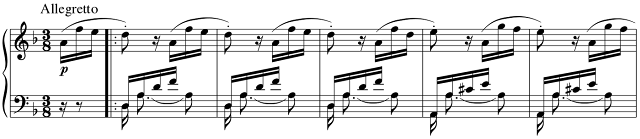

Personally, when considering the opening of

|

| Gretchen at her Spinning Wheel |

the third movement, I think of Schubert's "Gretchen am Spinnrade" (Gretchen at the Spinning Wheel), also inspired by a high-class poet, Goethe. The Schubert Lied, of course, had not been written yet. (Stay with me here. I promise to attach all of this to matters of fingering.)

I could over-simplify and suggest looking at an unedited edition. Oh, okay, I will.

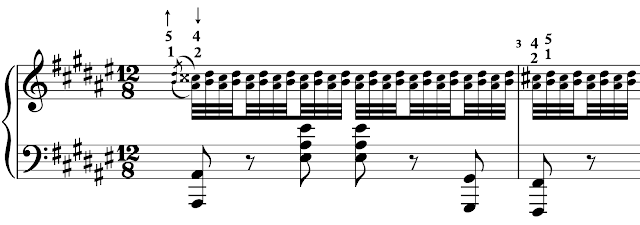

|

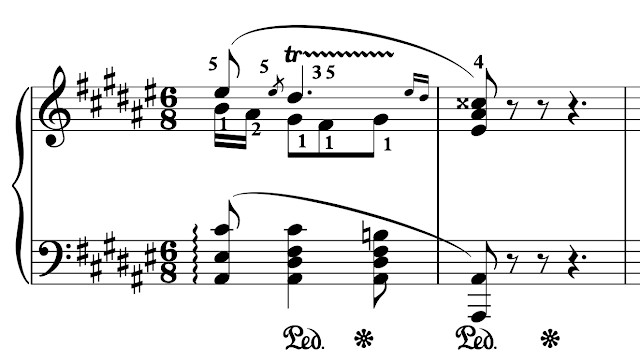

| Beethoven Op. 31, No. 2, MM 1-5 |

Notice that there are no pedal indications. Notice, too, and this is stylistically the most important, Beethoven gives the first bass note in each measure an extra stem and two flags. This bass-note is not a pedal point, meaning that it should not be held or caught in the pedal as some editions (Von Bülow, for example, or even Arrau) would have us do—and many fine contemporary pianists take that advice. I don't. Beethoven gives length instead to the A, which comes on the weakest part of the beat, yet has slightly more importance.

Now look at the melodic notes on the downbeats of each measure. Beethoven places a dot on these notes. At the risk of being excessively picky, I ask you to consider: Is this a staccato? If so, should it be the same length as the bass 16th? If that's so, why didn't he make it a 16th, too? Just lazy? Okay, I'll cut to the chase. I play the eighth-note it's full length with a slight melodic accent. We know that Beethoven used the dot sometimes in this way. (Have a look at the arpeggios on the first page of his Op. 110 sonata.)

Articulation is important to consider apropos of fingering because of the tiniest coordination issue that occurs between right and left hands when giving the right-hand eighth some length and accent while getting off of the 16th in the left hand. Once organized—and it really isn't difficult—the result is a more transparent, slightly askew, slightly agitated forward motion, not unlike the sound of a spinning wheel and its foot treadle. Gretchen is not at sea in a storm, but she is on the edge of madness as she spins.

|

| Schubert's "Gretchen am Spinnrade" |

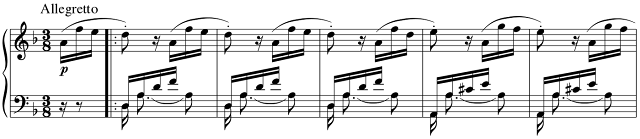

Editions differ as to how to finger the left hand, some seeming to ignore what I think are Beethoven's intentions. The issue hinges on which finger to use for the repeated A—4, 3 or 2. Here are my suggestions:

|

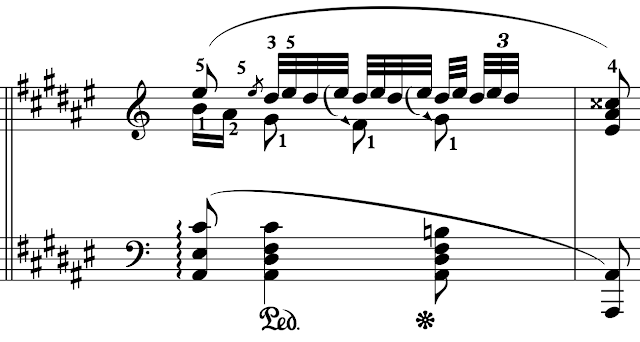

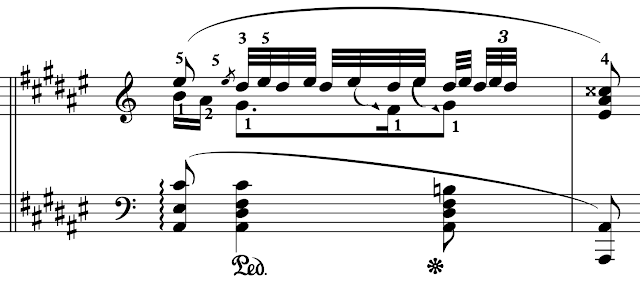

Beethoven Op.31, no.2 MM 1-5

My Fingering |

Since allegretto is not very fast, it is possible to detach the bass note and leap to the A with the fourth finger. I would never use three, as it creates a stretch to the second finger.

And in case you don't believe me regarding the articulation, look at measures nine to thirteen, where Beethoven changes his mind.

Some of my readers—well, a few—okay, two have wondered why my semi-autobiographical book The Grapefruit Cake Incident and Other Stories Instructive and Cautionary from a Musical Life isn't available on Kindle. This set me wondering, too. And, having put the correct wheels in motion, the said book is now available for direct download to your own device or visit Amazon here:

Some of my readers—well, a few—okay, two have wondered why my semi-autobiographical book The Grapefruit Cake Incident and Other Stories Instructive and Cautionary from a Musical Life isn't available on Kindle. This set me wondering, too. And, having put the correct wheels in motion, the said book is now available for direct download to your own device or visit Amazon here: Some of my readers—well, a few—okay, two have wondered why my semi-autobiographical book The Grapefruit Cake Incident and Other Stories Instructive and Cautionary from a Musical Life isn't available on Kindle. This set me wondering, too. And, having put the correct wheels in motion, the said book is now available for direct download to your own device or visit Amazon here:

Some of my readers—well, a few—okay, two have wondered why my semi-autobiographical book The Grapefruit Cake Incident and Other Stories Instructive and Cautionary from a Musical Life isn't available on Kindle. This set me wondering, too. And, having put the correct wheels in motion, the said book is now available for direct download to your own device or visit Amazon here: