|

| Chopin |

|

| Chromatic means "colorful." |

|

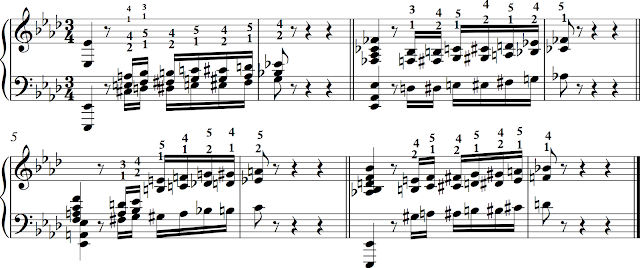

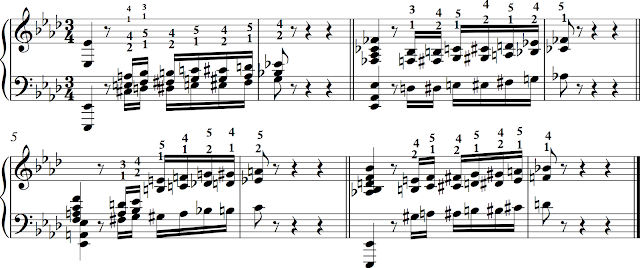

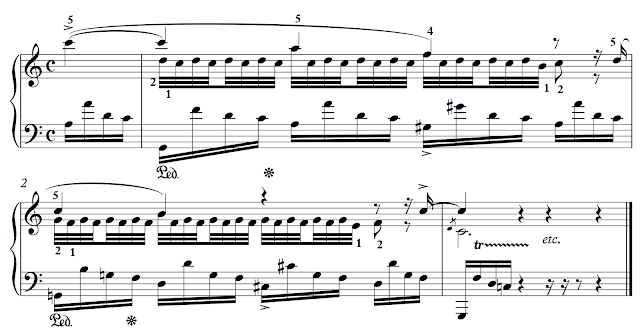

| Chopin Polonaise Chromatic Fourths |

Playing the Piano is Easy and Doesn't Hurt! Learn how to solve technical problems in Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin and all the other composers you want to play. Reconsider whether to spend time on exercises and etudes or music. Discover ways to avoid discomfort and injury and at the same time increase learning efficiency. How are fast octaves managed without strain? How are leaps achieved without seeming to move? And listen to great pianists of the past.

“Music is a moral law. It gives a soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, a charm to sadness, and life to everything. It is the essence of order, and leads to all that is good, just and beautiful, of which it is the invisible, but nevertheless dazzling, passionate, and eternal form.” Plato

|

| Chopin |

|

| Chromatic means "colorful." |

|

| Chopin Polonaise Chromatic Fourths |

|

| Chopin |

|

| No Stretching |

|

| It's an Illusion |

|

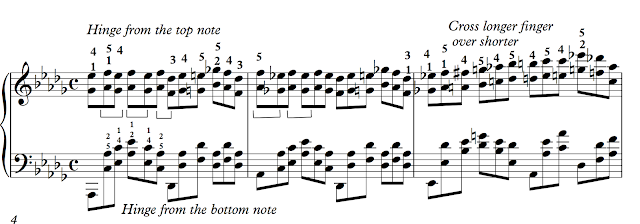

| Opening Measures of Op. 25, No. 8 |

|

| J.S. Bach |

|

| Bach A Minor English Suite, M 19 Prelude, Rotation |

|

| There's more to it than spinning. |

|

| Bach A Minor English Suite, M 19 Prelude, Verticalness |

|

| Robert Schumann |

|

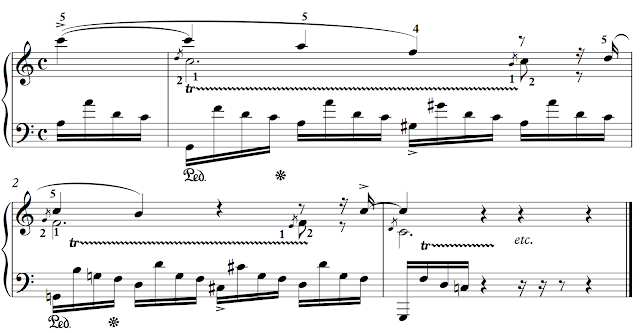

| As Written |

|

| As Played |

|

| Dimitri Kavalevsky |

|

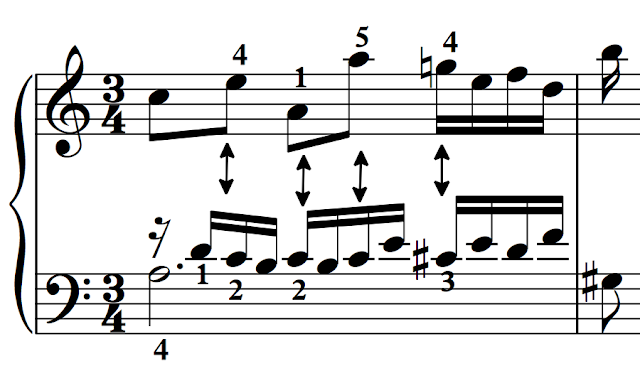

| Kabalevsky Sonatina, Op. 13, No. 1, Third Movement |

|

| Unbroken |

|

| Broken |

|

| Puzzler Solution |

|

| Arnold Dolmetsch (1858-1940). French-born but of Swiss origin |

|

| Bracket Symbols, Including Two Obsolete |