Even without reading Matthay's book, The Visible and Invisible in Piano Technique, much can be gleaned just from the title. It's my favorite title, I think, in the library of rhetoric on piano technique. I say this because much of what comes down to us from those proverbial old wives has to do with what can be observed in the playing of others.

|

| Tobias Matthay, England's Piano Sage |

Even fine players sometimes report the opposite of what they do, only because they think that's what they've seen others do, or perhaps what they think they do. These are the so-called natural players, the Mozarts and Mendelssohns, the Horowitzs and others who arrive from the womb as fully formed pianists. They didn't really go through the how-to period of development the way mortals do.

But how much can really be observed in an operation that is based largely on sensation? When observing a fine artist perform, never does the viewer sense a struggle—it all appears so easy. That's because it is easy, and most of what is observed is the "unobservable" that supports a fine, effortless technique. Yes, really, the structural underpinning of an efficient and brilliant technique is essentially invisible.

But how much can really be observed in an operation that is based largely on sensation? When observing a fine artist perform, never does the viewer sense a struggle—it all appears so easy. That's because it is easy, and most of what is observed is the "unobservable" that supports a fine, effortless technique. Yes, really, the structural underpinning of an efficient and brilliant technique is essentially invisible.

I mention this here because of a recent experience I had with a student who came for a consultation. She had just finished an undergraduate piano major at an important school of music complaining of various unpleasant, if not debilitating, sensations. Her playing is secure, completely fluent and in virtually every way the playing of a young artist on her way to a rewarding career. If she hadn't presented with complaints, I would not have thought to look for inconsistencies in her physical approach. Rather, I would have sat back and enjoyed her performance.

The usual indications of a flawed technique were totally absent. Her playing was immaculate, accurate and even thrilling. There were no moments of hesitation or fuzziness in passages. The tempos were appropriate and completely under control. So, what might be causing her discomfort? I know that it is not necessary to experience physical discomfort when playing the piano. In her case, though, she sometimes felt tingling, strain and wasn't always happy with the quality of the tone.

|

| The Piano is Down, Not Up |

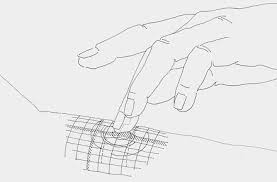

I asked her to play selected passages again. This time, on closer examination it was obvious that she extended her fingers into the air as if pointing. This was not a large gesture, but just enough to cause significant pulling away from the hand. I can hear my teacher now. "Dear," she would say, "the piano is down. The fingers only go up in order to come down again."

In other words, it is not efficient to isolate or separate the fingers from the hand individually and keep them pointing in the air, no matter how charming it may appear to the audience. When I pointed this out to her, the concept resonated and she was immediately able to incorporate a different strategy. We talked about how to apply forearm rotation (see iDemo tab above) to these passages.

She won't need to retrain particularly, but rather just be aware of this sensation, the sensation of being down in the key bed in order to be at "rest" and walk from note to note by transferring weight. This will reduce the strain she has experienced over a period of time and help her find the sound she wants. Remember, the quality and quantity of sound is controlled by the application of the arm. Fingers alone cannot provide this control, no matter what you hear from those old wives.