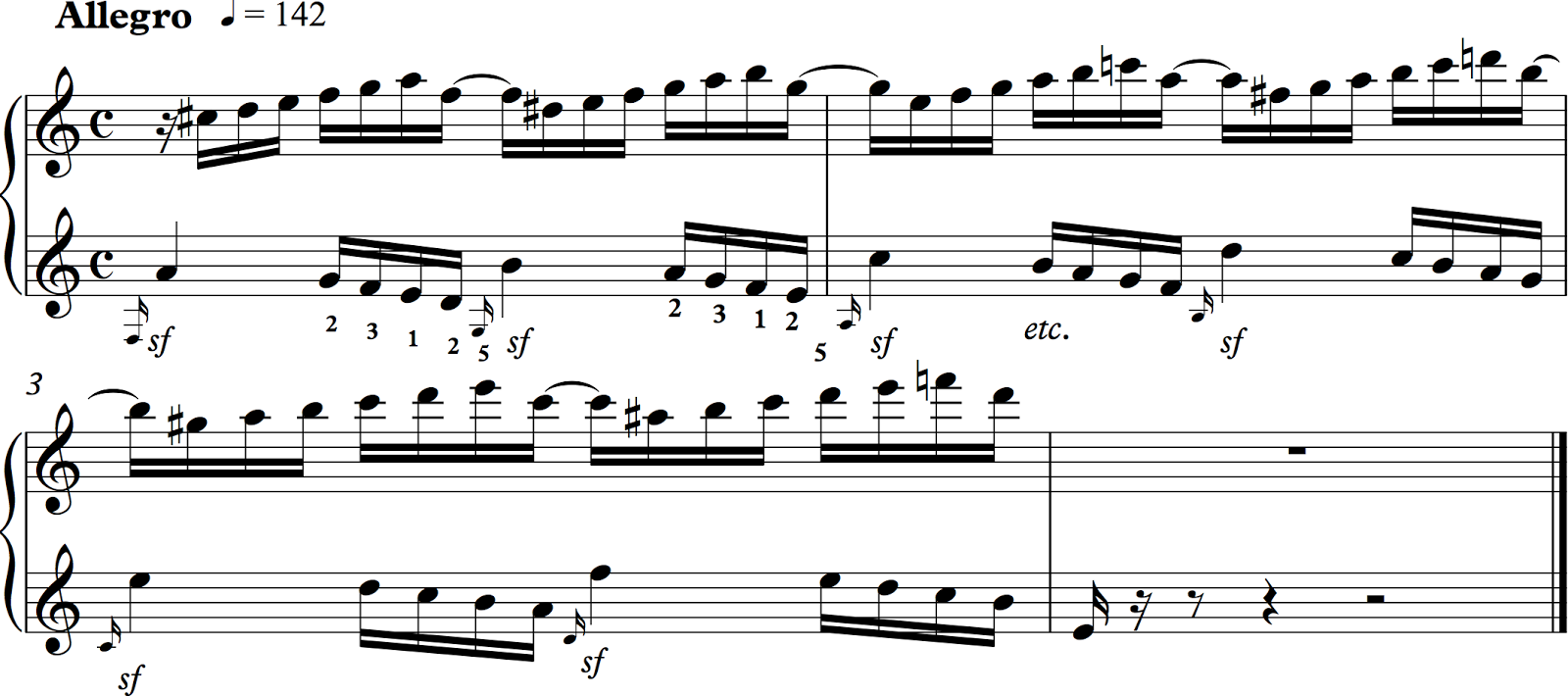

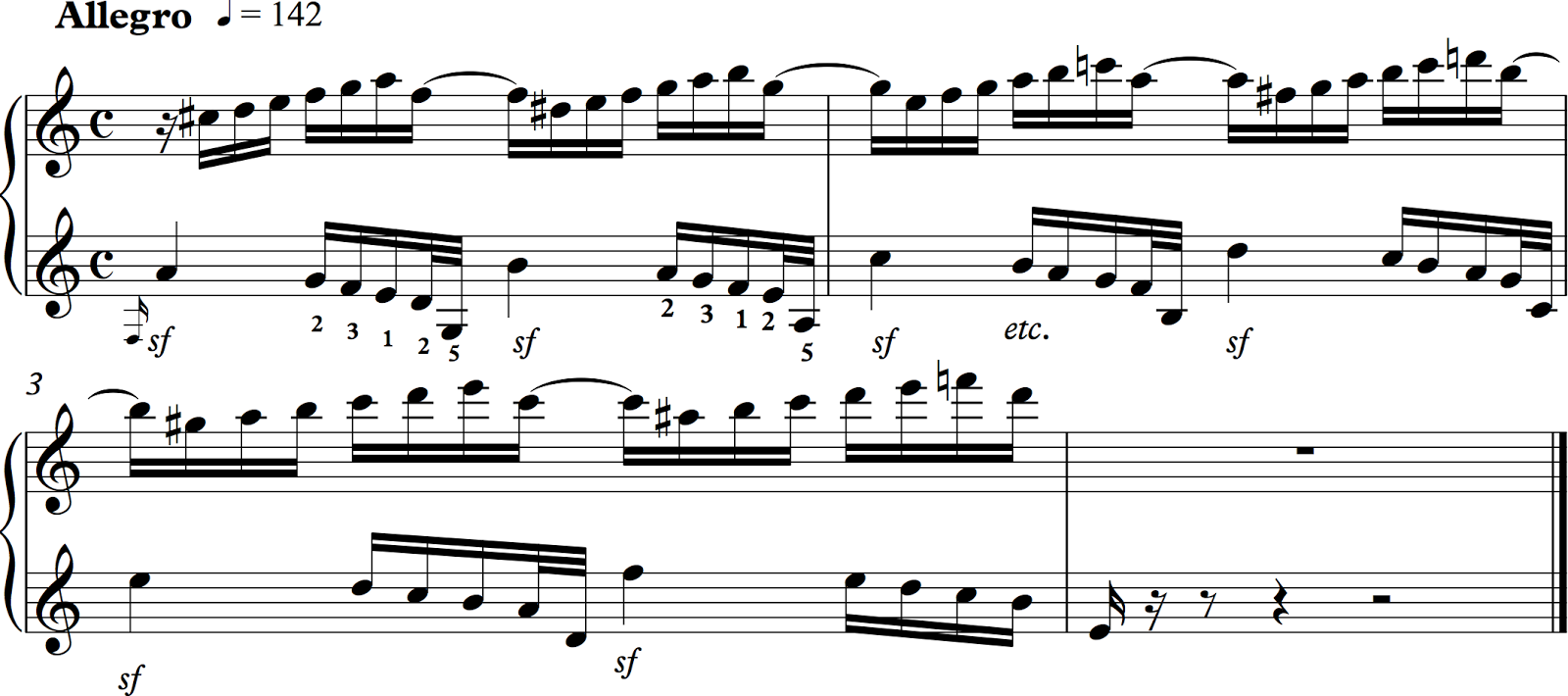

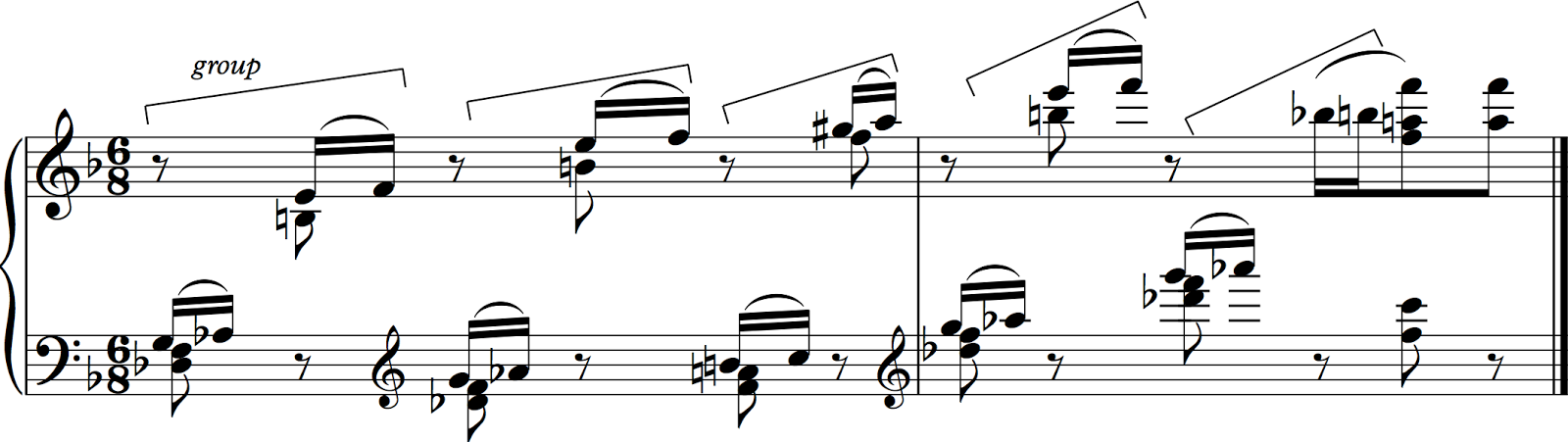

My husband and wife students came for their lessons the other day. One is considerably more advanced than the other, but both expressed interest in working on sight-reading. They brought with them my book, Guided Sight-Reading Practice at the Piano. (No, I don't make my students buy my books.) This collection of teacher-student duets takes the position that practicing with a partner can be helpful, a conclusion I arrived at for several reasons. Chances are that when playing with someone else, particularly someone with more experience, there will be more pressure to continue, without hesitating at problem spots. This automatically eliminates one of the chief impediments to reading. Also, a partner provides a steady pulse. And of course, it's always fun to make music together.

Well, almost always. In the midst of working through one of the examples, the Mrs. pointed out that they had had some disagreement over the process and apparently feelings were hurt—ever so slightly, she said with a smile. They suggested I might include on the cover a warning to married couples and significant others.

It was a joke. But this brought up a discussion of how to behave in ensemble rehearsals, the gist of which was that respectful dialog is always appropriate. I learned years ago that it's usually better in situations of musical disagreement—perhaps any disagreement—to resist beginning a sentence with the word you. So, couples, be forewarned.