|

| Frederick Chopin |

A student brought in this soulful nocturne, Op. 27, No. 1, the companion to the famous D-flat, No. 2 of the same opus. He observed that it's not as simple as it at first appears. Naturally, I took up my post as devil's advocate and asked what if we knew at a glance what the piece required technically, would it appear simple? This is another way of saying nothing is difficult if you know how, and learning how is, fortunately, the purpose of this blog.

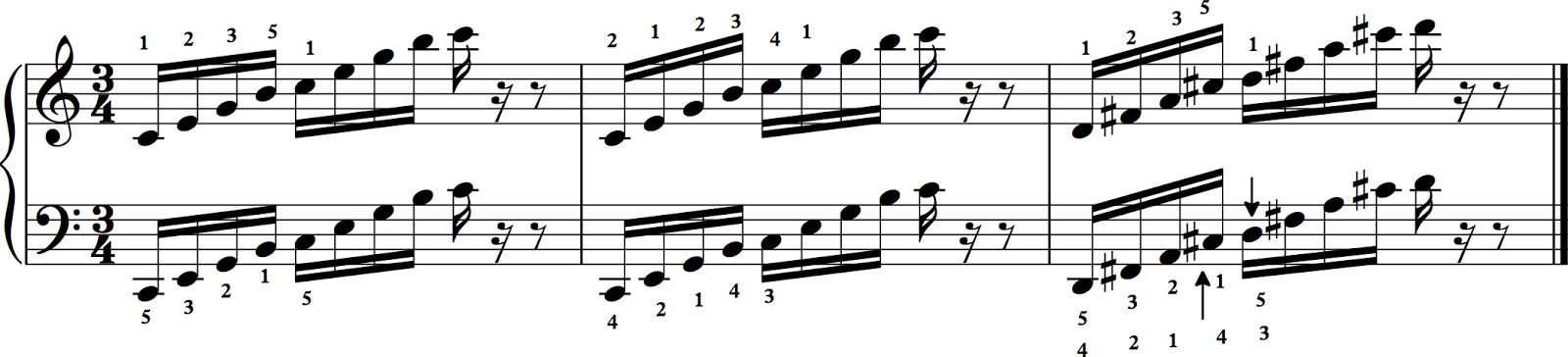

My student pointed to the leaping left hand in the three-four section marked appassionato:

|

| Chopin Nocturne, Op. 27, No. 1 (Click on example to enlarge.) |

|

| When leaping, always be sure to notice if there's water in the pool. That is, practice the landing. |

The first issue to consider is how to group the left-hand triplets. Instead of thinking 10ths, start each group with the thumb and continue thinking octaves. Always when leaping back and forth take care to group notes in such a way as to avoid feeling as if the arm is going in two directions. In speed this can cause a jamming of the forearm, a condition I call lockjaw of the arm (lockarm?) In this case we start with the thumb to 5 and allow the hand to fall back from 5, passively, to the new thumb. In measure 5 of the example, it's possible to take that last left-hand E-flat in the right hand, although not really necessary. Remember, there is a continual broadening (sostenuto). On the downbeat of measure 6, I take the left-hand A-flat with the right hand.

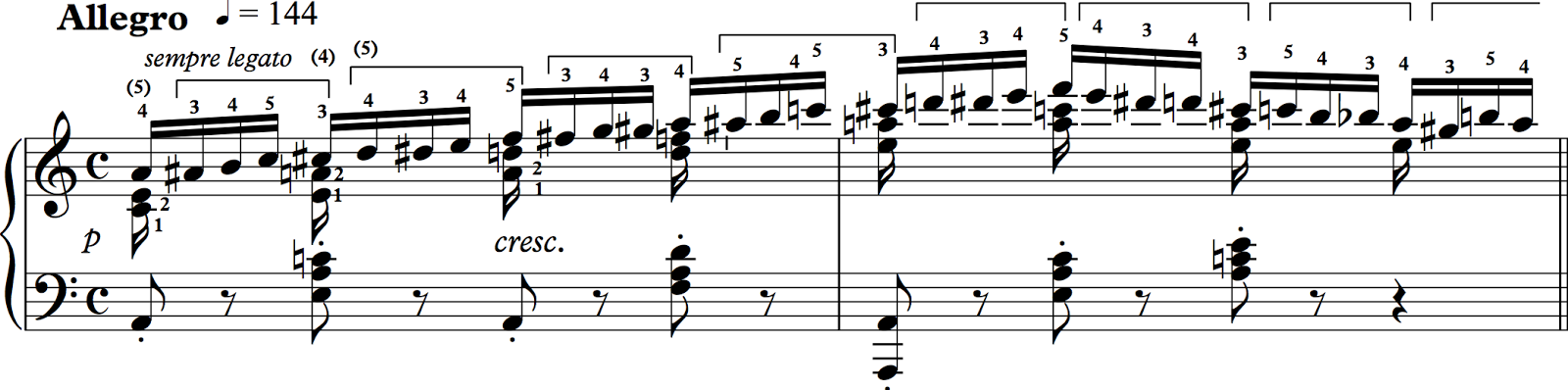

But wait! There's more! My student had another question. What about the forte section before that? Where the stretto begins? This is another left-hand leaping issue:

|

| Chopin Nocturne Op. 27, No. 1 (Click on example to enlarge.) |

|

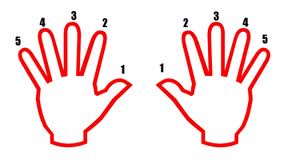

| Leaping is easy when you have a running start, when you consider how to do it. |

This one is a little harder to describe in words without demonstrating, but I'll try. Notice that most of each measure lies more or less under the hand, if we also shape to the wider intervals as they occur. These notes may be considered a group. The octave represents a separate voice and lies outside of the group of triplets. The technique is a combination of a leap from the octave by means of a pluck, or springing action, and a slight rotation toward the thumb. That is, the 5th finger is like a hinge from which the 3rd finger rotates toward its landing place on the F-double sharp. The feeling is of 5 moving to 3. Once the hand is balanced with 3 on its note, it plays the neighboring notes in succession before opening to accommodate the ever widening intervals played by the thumb. Take care that the hand doesn't remain in an open position.

The last left-hand note in measure one sends the hand to the following octave by means of a pluck and a rotation. This time 3 is the hinge, which allows the hand to open to the left and land on the octave. The feeling is 3 moving to thumb. Give the octave a little time. By that I mean go to it as if you plan to stay on it, which of course you won't.