Okay, the tempo is actually andante con moto (moderately slowly but with motion). Even so, it's only that and doesn't change much except for a few authorized slowings down and speedings up. Really. Look at the score.

Okay, the tempo is actually andante con moto (moderately slowly but with motion). Even so, it's only that and doesn't change much except for a few authorized slowings down and speedings up. Really. Look at the score. Coincidental to my restudying of Chopin's F Minor Ballade, the other day I came upon a FaceBook post offering an historical recording of Glenn Gould playing Beethoven's Appassionata, first movement. The eccentric genius plays at about half tempo, what I would call a good practice tempo. The

|

| Glenn Gould |

As I thumb through the pages of Chopin's Ballade, I notice no

|

| Frédéric Chopin |

I make this comparison because the issue is about trying our best as artists, as re-creators, to realize the composer's intentions, keeping in mind that a composer like Chopin, for example, has it over us as a creative genius. Regrettably, I'm not able to declare that any of the pianists I've heard had, like Gould, an educational purpose in mind as they disregarded Chopin's instruction—or anything at all in mind, except perhaps, and I think I'm being generous here, to amaze their listeners.

I'm thinking now of the passage beginning in measure 100, the onset of a development. Yes. Chopin thinks Classically. (Notice the capital 'C'.) This is all the more reason to think of a more consistent (not rigid) tempo. Here the composer writes a tempo. As we all know, this means return to the main tempo—which in this case is after a ritardando—not take a new one. Many pianists take off like a Czerny machine gone mad, but these passages are so much more meaningful than that and take on a remarkable expressiveness when played more or less in tempo—the indicated tempo—and with lyrical intent.

|

| Chopin's F Minor Ballade, MM 100-103 (The 'a' of a tempo is in the previous measure.) |

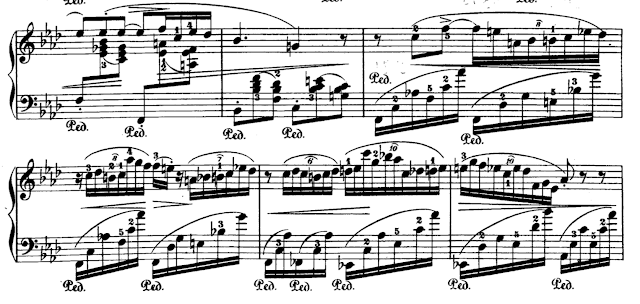

At the variation beginning in measure 152—yes, we have variations on a theme, another Classical convention—which is also typically played too fast. The melismas should each be allowed to speak for themselves, not pressed together like a glissando.

|

| Chopin's F Minor Ballade, MM 150-155 |

Even the etude-like passage in measure 191 (think 'Ocean' Etude) doesn't need to speed up, though I think Chopin might approve a slight forward tilt. There is no change of tempo indicated in the score. If this passage becomes too climactic, what are we going to do with the coda? The coda, by the way, has no tempo change, either. This is fortunate because it can be sticky to play cleanly, and we do want to hear the new material. (Richter, whom I admire greatly, plays so fast one can't hear anything.)

|

| Chopin's F Minor Ballade, MM 190-193 |

So, aside from a stretto in measure 199 and an accelerando from measure 227 to the end, there are no indications from the composer to make significant tempo changes.

Okay, I hear the "but, but..." Yes, Chopin's music is nothing if not flexible, like his hands, apparently. But we are not talking here about the so-called "tempo rubato", referring to the rhythmic relationship of the hands, which can be "out of phase." We learn

|

| Karol Mikuli |

No comments:

Post a Comment